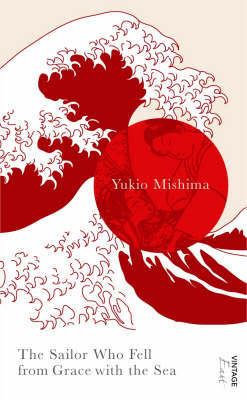

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea

Yukio Mishima

Trans. John Nathan

London, Vintage, 1999, 181p

I found my way to this book via the David Bowie exhibition at the V&A - apparently, it was one of many things that inspired the musical legend. And because I have loved the Japanese literature I have read in the past, and because I love Bowie, I thought I couldn't help but love Mishima.

However, The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea was somewhat disappointing. I suspect this is because I had such high expectations.

During a warm summer, a sailor begins a love affair. Fusako and Ryuji are caught up in the romance of it all - the secretive nights spent together whilst he is docked. After three days, Ryuji must depart, and he is filled with the glory of his love.

Meanwhile, Fusako's young son, Noboru, finds a peep-hole through which he can see his mother's room. He flits between admiration and resentment towards the sailor - admiration, because Noburo loves the sea and Ryiju can answer all his questions about his adventures; and resentment, because Ryuji fails to fulfill Noboru's ideas about how a sailor should be.

In the winter, Ryuji returns to land, and decides to give up his sea-faring life to marry Fusako. Noboru is furious that Ryuji has failed him, and plots his revenge.

I hesitated before I wrote this review simply because I do not feel I really understood the novel. I cannot get a grip on Mishima's motives and meaning, which, for an English graduate, is infuriating. I also do not know whether or not I enjoyed it.

The pace of the novel is rather slow: although the story does not drag as such, it is predominantly descriptive until the last quarter. Yet some of the descriptive scenes are simply magnificent beautiful. The novel opens with Noboru watching his mother undress - a moment which is disturbing and beautiful in equal measure. The language, or rather the translation of the language, is peaceful and precise, pinpointing the wonder of everyday things, including the human body.

The sea is a powerful symbol in this novel. For both Noboru and Ryuji, it represents freedom and possibility. Ryuji recalls the time when he chose to be a sailor, escaping to the sea for a chance of glory. Noboru has this choice ahead of him, but his love of ships suggests he wishes to escape, too. Thus, when Ryuji gives up sailing, he gives up glory and hope. He is emasculated.

Mishima is an incredibly dark writer, creating a group of thirteen-year old boys much like those in The Lord of the Flies: they are malicious, dangerous, and very intelligent. They have assigned themselves the role of saving humanity through brutality, seeing chaos as the only way to recreate existence. Having read a up a little on Yukio Mishima, I am still unclear if this is how he really views life and childhood, or if his novel is some sort of critique explored through these children.

I think this terrible darkness is what distanced me from this novel - I simply could not understand the children's motivations or actions. The evil was excessive to the point where the whole novel felt like a fantasy, and yet I think Mishima was searching for truth.

In my confusion, I want to read more of Mishima's work and to understand him better. He is haunting me. In this way, I suppose, Mishima has succeeded as a novelist.

No comments:

Post a Comment