Showing posts with label feminism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label feminism. Show all posts

Sunday, 1 March 2015

How to Build a Girl

How to Build a Girl

Caitlin Moran

I had almost neglected to write this review, seeing as it has been so over-reviewed already, but when I saw a friend reading it and laughing all the way through, I felt the need to offer my thoughts.

All those who know Caitlin Moran know her story by now - a clever girl raised on a council estate who lands a teenage writing prize and goes on to blag a column in The Times. Moran insists that How to Build a Girl is fiction, but it is hard to distance this novel from her own reality.

But it is not the plot of this novel that I want to celebrate, rather the little snippets of hilarity that are simultaneously completely familiar and obsurely unique. The teenage self-consiousness that convinces Johanna Morrigan she is singularly responsible for her family's poverty. The misreading of social convention that makes dressing solely in black seem like the best idea, and her mother's concern that she is acting like a dark crow that has decended upon the household. The naivety that allows her to have so much sex and so few orgasims.

Whether or not you like that fact that Moran seems to only write about one thing, you cannot deny the fact that she is honest, realistic and frankly hilarious.

Wednesday, 10 December 2014

Not That Kind of Girl

Not That Kind of Girl

Lena Dunham

London, Fourth Estate, 2014, 265p

When I found myself painfully jealous of a friend who was reading this book that I realised I had to get a copy. Lena Dunham's biography has caused some controversy already, and although I am not a religious watcher of 'Girls', I must confess I am intrigued by her.

Not That Kind of Girl is a funny, intelligent and sometimes disturbing account of Dunham's life so far. She talks about health, family and romance, and everything in between. She tells the reader she is a girl with a "keen interest in having it all", and this book is her story from "the front line of that struggle".

Dunham's youth is uniquely peculiar to me. She was born to artistic, liberal parents in New York, and her eccentricity and individuality have always been encouraged. In places, it sounds like she has low self-esteem (for example, when she discusses the common plight of the young woman who settles for a non-relationship with a guy who is clearly not good enough); and at other points, she explodes with self-assurance and good advice.

I had been warned that this biography is far from uplifting, but it was darker than I had expected, with confessions about her reliance on her therapist and descriptions of rubbish relationships. But within those moments that make your heart break, there are episodes that make you laugh out loud. Mostly, I simply admire her honesty.

I am conscious I am going through a phase of reading biographies of this kind - those of young, successful, strong women in comedy (see my recent review of Mindy Kaling's book). And I cannot wait to read Amy Poehler's recent release! With each of these women, I find some things to relate to and some things with which I disagree, but what my readings are demonstrating is that the female experience is varied and unique to each person - how can anyone stereotype about women when we are all so different?

Thanks to Jay for inspiration.

Monday, 1 December 2014

Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me?

Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (And Other Concerns)

Mindy Kaling

New York, Ebury, 2013, 223p

I hugely enjoyed my time with Mindy Kaling. Part of me wants to call her my guilty pleasure, but I have nothing to be ashamed of - I love her writing and acting; if I was a girly girl, I would want to be like her: self assured, embarrassed by nothing, beautiful.

Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? is Kaling's hilarious biography. She recounts her school days, her wild ambition coupled with boring jobs, and her eventual success when she joined the writers of The Office. Her book combines extended lists with long prose accounts, and carries the air of someone trying not to give advice (and sort of failing).

Kaling possesses a ridiculous amount of passion and knowledge about comedy, listing her favourite comedy moments and recounting friendships that just didn't work out because the other person wasn't as in to it as she is. Since writing this book, Kaling has created her own sitcom, The Mindy Project, and I would have loved this book to contain more of her crazy confessions about this.

A few days after having finished this book, I am still laughing as I recall little snippets of her humour. In particular, I have adopted Kaling's approach to jogging, which is to fantastise about imaginary revenge scenarios. Despite initially finding this idea hilarious, in practice it has proven to really occupy the mind and distract from the pain of running.

Kaling is open and honest with her reader, telling her most awkward moments and biggest celebrity crushes. But throughout, she is explicitly happy with who she is - she is unapologetic and doesn't really care what anyone thinks, despite confessing to a fascinating with fashion and dieting, interests conventionally possessed by those who care too much what other people thinks. In this way, she has even challenged some of the subconscious presumptions I had about women. She doesn't try and claim that her experiences are the same as any other woman's experiences, and that is what I love most.

Friday, 18 July 2014

The Invention of Wings

Sue Monk Kidd

Tinder, 2014, 410p

I received this book some months ago as a free proof via Twitter from the wonderful people at Tinder publishing. I love Sue Monk Kidd, having read The Secret Life of Bees in my teens whilst studying the slave trade - it added a personal, emotional element to my understanding of the suffering and desperation of those who were victims of slavery.

The Invention of Wings is a story told by Sarah Grimke, the daughter of an aristocratic landowner, and Hetty Handful, a slave of the Grimke household. When Hetty is given to Sarah as a present, Sarah tries to give her back, uncomfortable with the idea of owning another person. She is a forward thinking and ambitious young girl, determined to follow her father into the legal profession. But her parents refuse to accept her liberal ways, and bestow Hetty upon Sarah anyway. Sarah tries to be kind to Hetty, but sometimes finds slavery too ingrained in her way of life. Hetty, meanwhile, tells us the story of her mother and her grandmother - how their talents as seamstresses have helped them become house slaves, rather than those who work the fields. Yet, Hetty's mother has a streak of danger running through her blood, and her attempts to defy their masters and liberate themselves from slavery end in the harshest of punishments.

As the two girls grow older, their paths diverge, but their stories remain intertwined. Sarah becomes an advocate for the abolition cause, talking at meetings and writing pamphlets with her sister, Nina, eventually stumbling upon the suffragette cause when their public speaking becomes suppressed by their gender. And Hetty continues to work for the Grimke family, but continues to dream of freedom.

In her closing note, Sue Monk Kidd informs her reader that the story is based on a true story - that of Sarah and Angelina Grimke, sisters who fought for abolition and suffrage, tending against their Southern upbringing. Much poetic license has been used, including Hetty's life, adding an element of contrast to the story of the wealthy white woman. The author brings in much historical information, adding volume and texture to her account of life in nineteenth century America.

And the writing is simply beautiful - within the first few pages you have been transported back two hundred years, and you can see every detail, every stitch that Hetty sews. One line that particularly stood out for me was towards the end of the book, where Hetty describes her aged mistress: "She has lines around her eyes like dart seams and silver thread in her hair, but she was the same."

Their stories are of hardship and tragedy, but their hope is uplifting. Sue Monk Kidd notes that the records show that Sarah was more reluctant about some of her actions than this novel suggests, but in a time when it must have felt like the whole world was against them, I consider Sarah's bravery and Hetty's determination to be inspiring.

Friday, 23 May 2014

Transformatrix

Transformatrix

Patience Agbabi

Edinburgh, Payback, 2000, 78p

No poet packs such a punch as Patience Agbabi. From the opening line of this collection, she calls her reader to battle, seeps rhythm through their bones, and empowers one to be strong.

Transformatrix contains a series of poems designed for performance - reading them in your head is not good enough. They are written to be shouted and sung, with unusual rhythm and unconventional rhyme that only reveals itself through the spoken word.

The collection explores Agbabi's observations about contemporary society - about race, poverty, femininity and sexuality. Some are funny and some are angry, but all are passionate.

The first poem is one of my favourites - 'Prologue'. As with a novel, the first line of a poetry anthology should grip you and make you want to read more, and with 'Prologue', Agbabi has written a poem full of pizzaz and joy. To read it aloud, you can indulge in the magic of language as the words roll off your tongue, each carefully crafted and executed. You can feel the influence of British music and culture,

The book is broken down into sections; the focus of many being women - powerful women, subordinated women, women in love. Each little poem tells it's own story, and when collected together in sections, each part of the book tells a wider story. As a whole, Transformatrix is uplifting, exciting and invigorating.

Wednesday, 30 April 2014

The Handmaid's Tale

The Handmaid's Tale

Margaret Atwood

London, Vintage, 1985, 324p

This is one of those books I have been meaning to read for a long time - the kind of book my non-librarian friends condemn me for not having read. But at last, I can stop feeling guilty - instead, I now feel haunted by one of the darkest novels I have ever read.

In the Republic of Gilead, the roles of all are clearly defined by a strict social structure. Commanders and their wives occupy places of power, served by Marthas and Handmaids. Any rebels are swiftly removed from society, the punishment typically being death. Offred is a Handmaid, and her role is to enable procreation - she's are subject to harsh rules about sexuality and sensuality, dressed always in long dark robes.

But a repressive state does not prevent Offred of dreaming of her past and hoping for the future. She had a child, once, and a husband, and longs to be reunited with them; but fear is a powerful deterrent.

Margaret Atwood defines her writing as speculative fiction, as, unlike science fiction, the world she creates could really happen. As Offred describes, the transition from the contemporary society in which her reader lives into the Republic was slow and smooth, beginning with identity cards and scienfitic developments in relation to DNA. As such, the world Atwood has created is plausible, it could become our reality in the future.

The Handmaid's Tale is a sharp, perceptive novel about structures of power in modern America. Atwood explores issues of sexuality and desire, highlighting the impossibility of a 'moral' state, in part due to the complexity of defining what is moral. Her prose is incredibly witty and readable, drawing you into Offred's world and haunting you with the possibility of this dark, repressive future - and slowly revealing how it came to be.

Monday, 17 February 2014

What Are We Fighting For?

What Are We Fighting For?

Brian Moses and Roger Stevens

London, Macmillan, 2014, 112p

Seeing as this year marks the centenary of The Great War, I am anticipating many publications to deal with this subject. What Are We Fighting For is the first I have come across: a varied, original collection of poems written and collated by Brian Moses and Roger Stevens.

At first, I thought this collection would be an anthology of existing poems, and was disappointed to find that it was in fact some new poems written by contemporary poets. I felt a little concerned that they had no authority on the subject and that the writing would be idealised or exaggerated.

But I was pleasantly surprised to find poetry that covered a variety of subjects in a factual and informative way. The collection felt a little like a history book, giving information about life in the trenches, the causes of conflict, and what things were like for those people left at home. Some of the poems are supported with snippets of factual information, explaining what realities the stories relate to. And each poem is just that - a little story about a person or a place or an event, taken from history and embelleshed in a more accessible manner.

This book contains poems about all conflict - from the First and Second World War, right through to modern day conflicts. The final section seems more childlike and innocent, exploring the world through the eyes of young characters who do not see war in their back garden, but are sometimes vaguely aware of world news and battles fought overseas. There is even a poem about a playground fight, as Moses and Stevens cast doubt on conflict at all levels.

So despite not meeting my initial expectations, I found this collection of new poems to be touching, leaving the reader with food for thought; though I expect there to be a lot more high quality writing on this subject to be revealed over the next few years.

Labels:

anthology,

boyhood,

death,

drama,

fact-based,

family,

feminism,

friendship,

historical,

morality,

poetry,

war

Sunday, 19 January 2014

The Bell Jar

The Bell Jar

Sylvia Plath

London, Vintage, 2005, 234p

I have a whole lotta love for Sylvia Plath, despite her reputation as being rather depressing. I first read The Bell Jar during A-Level for my coursework, for which I set about on a focused study of the themes of the novel, with a particular emphasis upon gender. It has been such a long time since I read it that it felt like reading it for the first time, and again I savoured every minute.

Esther Greenwood is spending a summer in New York, having won a writing scholarship to work at a reputable fashion magazine. Holed up in a female-only hotel full of fellow winners, she is trying to make the most of this opportunity, but finds herself overwhelmed by the hypocrisy of world in which she finds herself. On returning to suburban Boston, Esther is exhausted but completely unable to sleep, and spirals into depression as she contemplates her future prospects.

First published in 1963, The Bell Jar outlines the plight of the educated, middle class young woman in a society with offers limited opportunities outside domesticity. Esther is surrounded by women who work under the thumb of powerful men or gave up their jobs to marry. When she thinks of her future, she knows that whatever decisions she makes will cut off a hundred other opportunities, and she finds herself unable to act. The feeling of completely lack of control overwhelms Esther, making her feel stifled and suppressed, like she is trapped beneath a bell jar.

Reading today, with a better understanding about mental health, the story of Esther Greenwood is disturbing and frustrating. She finds herself isolated, unable to talk to anyone about how she feels; and when she tries to explain, she is patronised and mocked. Contemporary treatments included electroconvulsive therapy, a traumatising experience that offers no solution to Esther's feelings.

The story is thought to be semi-autobiographical, with Esther's life unfolding in a similar way to Sylvia Plath's. But I always felt this novel was more universal than that, appealing to many young people, growing up unsure of what lies ahead.

But there is such beauty in Esther's sorrow. The imagery she uses is profoundly unique, demonstrating the complexity of the depressed mind. It is almost as if she sees more than the rest of us, and this deep awareness sinks her into melancholy. The Internet is flooded with meaningful quotations from the novel, adopted by readers as a reflection of their own lives.

Reading this again, I was able to distance myself from Esther's story, whereas I used to read too deeply into it and relate it to my own life. Now, I am able to note the beauty in the melancholy, seeing the nuances of the language and the detail in the images. For me, this novel is not a sad one, but one of incredible originality, poignancy and beauty.

Thursday, 5 December 2013

Persuasion

Persuasion

Jane Austen

London, Penguin, 2007, 272p

My book hangover is cured!

If anyone was going to fix me, it had to be Jane Austen. Persuasion is my all time favourite book. It is like comfort food to me - warm, relaxing, like spending an evening with an old friend. I have read it a million times, and every time I have laughed and cried and gotten heart burn from forgetting to breathe.

When the lives of Anne Eliot and Frederick Wentworth cross again, eight years after she was persuaded to break off their engagement, neither can be sure what the other now feels. Anne is a gentle, intelligent and practical young woman; modest and quiet unlike her humoursly self-centered family. And Wentworth is noble and agreeable, bursting with emotions but terrible at revealing them.

So like every other perfect couple in history, they convince themselves that the other no longer loves them. Frederick's friendly attention to Anne's nieces convince her that he must love another; and her determined modesty makes him believe she could never return his affections. Oh, why don't they just tell each other!?

And this is exactly why I get heart burn. Austen writes so well - building the suspence, carrying the novel through stolen glances and mistaken actions. I find myself drawn right into the room with Anne and Wentworth, watching their every move, trying to be patient, knowing they will come together eventually.

I have oodles of respect and love for Jane Austen. She is so clever and timeless. Her characters are vivid and true - we all know someone like the people in this story. And the locations remain alive today, places like Bath and Lyme Regis, still classically regent. This book mocks the foolish ignorance of the upper classes, challenges the percieved differences between the sexes, and celebrates the sensibility of educated women.

But the most incredible element in this novel is that letter - Captain Wentworth's confession. I can say no more; you must read Persuasion to understand.

Wednesday, 2 October 2013

Be Awesome

Be Awesome

Hadley Freeman

London, HarperCollins, 2013, 266p

I have been reluctant to finish this book - I wanted it to go on forever. But even the best things must eventually come to an end. I just wish Hadley Freeman was my friend.

Be Awesome is a bold, bright guide to life for intelligent, modern women. Freeman discusses fashion, culture and society, listing her ten favourite books and offering answers to all your dating woes. Her message is to be true to yourself and she gently coaxes you, the reader, to realise you are awesome.

This book is unashamedly feminist. Today, feminism seems to be getting a bad reputation and few women want to associate themselves with this label. As Hadley notes, this is madness. Feminism is about equality: it is about variety and identity. For both men and women, it is about being brave enough to be who you want to be and/or who you are: it is no more about hiding behind gender stereotypes or being ashamed of success than it is about bra burning or acting 'masculine'.

I have often found myself frustrated by some of the issues explored in this book and unable to explain why. If everyone read Be Awesome, they might have a better understanding of some of the things in my head. Like why do women over-analyse dates and relationships, trying to decipher the meanings of their companions every word and action? Why does it matter so much? The important thing is whether you like him, surely? And why do some newspapers simultaneously chastise one celebrity for being too thin whilst another is too fat. And why do so many movies contain nameless, personality-free female characters who only ever chat about men; unless the female is the protagonist, in which case she will only find "happiness" when she settles down to marry and have children in suburbia. Because of course we could never have it all!

There is so much to admire about this book and it's author: from the witty tone to the intelligent approach to every tiny detail. It is honest and observant, and I found it perfectly expresses so many of issues I struggle to articulate, including why Persuasion is one of the best novels ever written.

Also, there are references to The Princess Bride throughout - who doesn't love the Dread Pirate Roberts?

This blog post is preemptively dedicated to all the people to whom I will recommend this book for the rest of my life, starting with award-winning Esme.

Labels:

biography,

feminism,

friendship,

funny,

girlhood,

heroines,

LGBT,

non-fiction,

politics,

women

Monday, 12 August 2013

The Fat Black Woman's Poems

The Fat Black Woman's Poems

London, Virago, 1984, p85

London, Virago, 1984, p85

I have opened this collection several times over the course of the last couple of weeks, searching for and finding new meanings and details with every read.

The Fat Black Woman's Poems is a refreshing and challenging look at the world through the eyes of Grace Nichols. It consists of four different collections, each with a different tone and theme running through. The first is the title collection - a series of passionate poems, sometimes angry, sometimes comic, about the experiences of a fat black woman. She contrasts ideas of Western beauty with images of African culture and climate. Nichols isn't resentful or self-loathing, but joyous and confident, full of the wonder of womanhood. She is proud.

The collections that follow are similarly loud. Some are about London life, set in conflict against her African heritage. Some are about family and friends, full of affection and admiration. And some are political, exploring the history of black lives, from slavery to racism and everything surrounding these subjects.

I love Grace Nichols confidence. She is strong and brave, and her power is perpetuated through her words.

This is an inspiring collection, both in terms of its subject and its form. Nichols is unconventional, refusing to conform to standard rhyme, structure or language. But in this way, she demonstrates that poetry can be whatever you want it to be.

Grace Nichols

The collections that follow are similarly loud. Some are about London life, set in conflict against her African heritage. Some are about family and friends, full of affection and admiration. And some are political, exploring the history of black lives, from slavery to racism and everything surrounding these subjects.

I love Grace Nichols confidence. She is strong and brave, and her power is perpetuated through her words.

This is an inspiring collection, both in terms of its subject and its form. Nichols is unconventional, refusing to conform to standard rhyme, structure or language. But in this way, she demonstrates that poetry can be whatever you want it to be.

Labels:

fact-based,

family,

feminism,

funny,

literary,

poetry,

politics,

race,

religion,

slavery,

spiritual

Monday, 29 July 2013

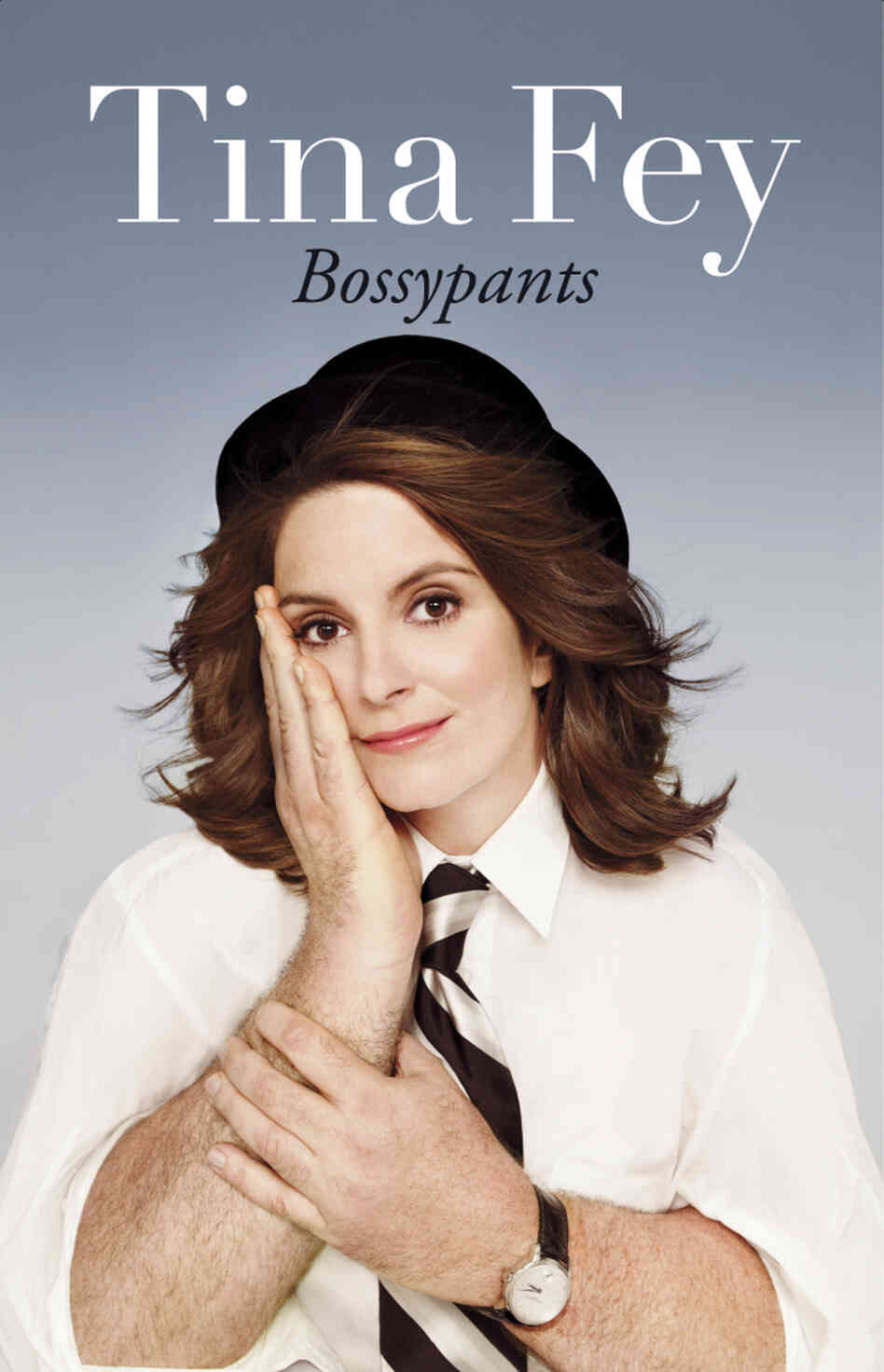

Bossypants

Bossypants

Tina Fey

London, Sphere, 2012, 304p

I love Tina Fey more than I love cheese. Now, you may not realise what a big deal this is for me. I do not say such things lightly. For me to love something more than I love cheese, it means that I could not live without it. Cheese is my favourite food group - you are never restricted by it, but can consume it all times of day and night, on or alongside all sorts of meals. There are very few things I love more than cheese, but I could not live in a world without Tina Fey.

And this is her autobiography, gifted to me by a friend who knows me a little to well, and read at least five times since, often whilst giggling to myself. Before you even start reading, you just need to take a glimpse at the blurb to realise how brilliant this is going to be:

See!?!"Once in a generation, a woman comes along who changes everything. Tina Fey is not that woman, but she met that woman once and acted weird around her."

If you are already a fan of Tina Fey, you will love this. It is ridiculously funny, painfully intelligent, and of course, never particularly high brow. And if you have no idea who I am talking about (shame on you), you will find something in these pages of comedy writing that makes you feel uncharacteristically good about being you.

Somehow, Fey has managed to produce the least revealing autobiography in history. She talks about her childhood, her college years, and her honeymoon, but in a way that leaves you longing for more, wishing you could be her friend. She pokes fun at the tell-all, cliche-ridden biographies out there, unable to take seriously the task of writing her life story. She refuses

to wallow in the memories of her childhood, which she found to be particularly enjoyable. She was neither the lonely, geeky schoolgirl or the sex-crazed teenager. She never suffered from parental neglect or over-parenting. She is just herself.

And she makes it okay for her readers to be whoever they happen to be. In one chapter, she lists all the things that can apparently be wrong with a woman, but shifts the focus in a follow up list where she talks about the things she likes about herself. No self-pity, no plastic surgery woes, just the realities of life.

Fey also challenges the assumption that she has it all. In 30 Rock, Liz Lemon regularly dreams of having it all, but is stumped by a lack of boyfriend, lack of time, or simply lack of luck. Similarly, Fey rants about the impossible work-family balance, knowing how lucky she is to have a job she loves and a husband who supports her. But whilst at home, she is haunted by the work she has to do; and whilst at work, she wishes she was playing dress up with her daughter.

What I think I adore most about Fey is her ability to be sarcastically optimistic. By this, I mean that she never seems to be sad or bitter, but manages to perfect this matter-of-fact tones that implies that life is what it is, and sometimes, life sucks. She never raves about how lucky she is, or rants about how hard she has to work, but you can tell she is appreciative of all she has. She never claims it is easy being a woman in our contemporary society, but she still manages to quash any assumptions about modern woman you might have in the back of your mind. We are all different, and Tina Fey makes that okay.

This post is for Mr Christopher Mark Folwell, because those shoes are definitely bi-curious.

Monday, 22 July 2013

Suffragette

Suffragette: The Diary of Dollie Baxter, London, 1909-1913

Carol Drinkwater

St Helens, Scholastic, 2003, 224p

The 'My Story' series tell the tales of a number of historical events through the eyes of fictional contemporaries. The series includes accounts of the reign of Bloody Mary to the voyage of the Mayflower. This particular story is about a young teenage girl's experiences of the Suffrage movement in the beginning of the twentieth century.

Dollie Baxter is thirteen years old in 1909, when her benefactor passes away and she is left unsure of what her future holds. She was born and raised in the dockyards of London, an area of poverty and destitution, but was rescued by Lady Violet and placed in education. Now, she depends on the goodwill of Lady Violet's granddaughter, Flora, who is a suffragist, socialising with the most famous names in contemporary culture and feminism. Through Flora, Dollie learns what suffrage is all about,and joins the Women's Social and Political Union, the more radical, violent branch of the suffrage movement.

Although Dollie is a fictional character, she interacts with many people who were prominent members of society at the turn of the century. She crosses paths with feminist leaders, from Emily Wilding Davison to Christabel Pankhurst. She attends dinner parties alongside George Bernard Shaw and Katherine Mansfield. Reading this novel is like walking through a classy soiree of celebrities. Dollie's guardian is well connected, granting her the opportunities to be better educated, more aware, and to move up in the world.

However, since Dollie was born working class, she continues to carry the burden of her heritage. In the upper class London society, she is aware of the vast differences between herself and her friends. Her fight for equality is rooted in her past, as she fears what would have happened to her had she not been taken in by Lady Violet. Seeing her mother so dependent upon her father, she believes education and employment as the only way to free women from the power men. Her plight differs from that of her rich friends, as she acknowledges how lucky she is to have such opportunities.

But then, when she goes home to visit her mother, she finds anger and resentment awaiting her. Her mother refuses to accept charity from her wealthy daughter, and is reluctant to encourage her in the suffrage movement. And her siblings envy her, mocking her posh accent and well-to-do dress. Dollie is in-between, never fully belonging.

I think it can be really difficult to engage young people in history. With so many facts and figures and little link to our reality today, the subject can seem distant and unimportant. Of course, history teaches us valuable lessons, but if you have little history yourself, how can you be expected to appreciate how past experiences can help us in our future decisions and prevent us from repeating unnecessary mistakes? These fact-based stories, with young fictional protagonists surrounded by historical fact, offer a route into history for young people. Students need to be aware that they are not 100% accurate, but they will support their curriculum-based learning and hopefully fuel their interest to research further.

Thursday, 25 October 2012

Jane's Fame

Jane's Fame

Claire Harman

New York, Picador, 2011, 277p

Claire Harman write cleverly and confidently about the history of the celebrity of Jane Austen - her rise to becoming a well-known household name in the 21st century. She brings together and analyses various biographical accounts of Austen's life, offering new information as well as critiquing existing publications.

I found out some rather interesting facts whilst reading this; one of which was that Mark Twain and Ralph Waldo Emerson didn't rate Jane Austen. It upset me to think that my favourite writers didn't respect each other. I also found it interesting that Austen's novels were a popular subject of study when English Literature was first introduced into universities - her works were considered soft materials for a soft subject, which was predominantly studied by women. And yet, some of her most vocal admirers are / were men.

When reading her novels, I have always found Austen's lack of detail about places, dates and individual's features quite enticing - this has allowed me to imagine my own Captain Wentworth and Mr Tilney. However, Harman argues that this was Austen's attempt to avoid being trapped within a certain era. Many of her novels were published significantly later than written, and therefore could have easily become outdated and old fashioned. In avoiding specifics, Austen allows her stories to fall easily into any time period, so that readers of today can relate to her stories just as easily as her contemporary audience.

In this way, Austen has been adopted as the symbol for many causes. We still don't know much about her life - everything is speculation. Consequently, people can make assumptions, draw links, and use Austen as a figurehead for any cause. She can be paraded as a feminist role model, challenging patriarchal rules, as well as representing the stoicism and peace that the Tory party have used her for.

But that's what I like about Austen. She is different things to different people.

Sunday, 16 September 2012

Twelve Minutes to Midnight

Twelve Minutes to Midnight

Christopher Edge

London, Nosy Crow, 2012, 254p

Twelve Minutes to Midnight, set in 1899, is a story about a madness that sweeps through London, seeping into the lives of literary greats (Arthur Conan Doyle and H G Wells are referred to more than once). Penelope Treadwell is the author and editor of a penny journal, but hides behind the name of Montgomery Flinch.

Penelope is an inspiring hero. What I like about a lot of teen fiction is that the reader is regularly reminded that the hero is in fact only a child, or a teenager. In Penny's case, her youth and her gender prevent her from being able to independently investigate the recent phenomenon. Instead, she has to be escorted by her uncle or other unsuspecting gentlemen, who she drags along to Bedlam and into imminent danger. She, of course, is fearless.

I'm a bit of a sucker for Gothic literature, and I go weak at the knees when stories are set in the Victorian era, so this was an all-round winner. There are deadly spiders, ghostly noblewomen, and futuristic prophecies, all in a race against time.

I don't want to give too much away, because something I really enjoyed about this book was the twists and turns. I thought it was never going to end. At one point, Edge seemed to be tying all the strings together, but I still had 60 pages to read - and what a treat those pages were!

The aforementioned madness characterises itself in the scrawlings of its victims. Hence the repeated references to contemporary authors. When an individual falls under the spell of madness, they wake at twelve minutes to midnight and write on anything they can find. And what do they write? Prophecies of the coming century - increasing industrialisation, the invention of the airplane, wars, terrorist plots, and more. The reader may have to remind themselves that this novel is set in 1899, otherwise they may not understand the importance of the twentieth century events.

I had a lot of fun reading Twelve Minutes to Midnight - and that is something that can't really be said about a lot of books. It indulged my personal interests, but it was also well-written and addictive - I think it has something for everyone.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)