The Bunker Diary

Kevin Brooks

London, Penguin, 2013, 259p

The Bunker Diary

Kevin Brooks

London, Penguin, 2013, 259p

*Possible spoiler alert*

It is hard to write this blog without giving too much away - and I desperately do not want to give anything away, since I was given a little warning regarding how haunting and spine-chilling it is and I worry that too much information might detract from the tension of the story.

When Linus wakes up in an abandoned bunker, he is angry at himself for being tricked by a blind man who kidnapped him. He finds himself alone, but, with five empty rooms around him, suspects that this won't be for long. The only way in or out is a lift, which comes up and down at set times through the day. As time goes by, more people are sent down to join him, each from vastly different backgrounds, each having been tricked in strange and well-planned ways.

And they are being watched; there is no way out. Together, the captives work out how to communicate with their captor, but every attempt at escape seems wrought with punishment. They struggle to be civil with one another, especially in the context of this unusual situation. As the characters sink into desperation and depression, the reader is trapped with Linus in this underground dungeon.

I have not read any Kevin Brooks before, though I have always been intrigued by the packaging of his novels. In fitting with the dark trend running through this year's Carnegie list, The Bunker Diary is a strong contender, full of mystery, tragedy and a slither of hope.

To see the rest of my Carnegie reviews, click here.

Rooftoppers

Katherine Rundell

London, Faber & Faber, 2013, 278p

As I neared the end of this book, I had no idea how it would possibly come to it's conclusion with so few remaining pages. After a slow and leisurely build up, I was impressed that everything managed to come to a conclusion so quickly and smoothly.

When Sophie is orphaned in a shipwreck, she is adopted by the eccentric and loving Charles. He teaches her about books and dreams and she learns to never ignore a possible. But as she grows up, the authorities become increasingly concerned about whether it is appropriate for Charles to remain her guardian, as she is less feminine than is expected of her time. So hiding on rooftops from the authorities, Sophie sets out to find her mother, presumed lost in the wreck, but Sophie still has hope.

The opening of the novel is rather slow of pace - you are introduced to Charles and Sophie and their little domestic absurdities, which I loved. For Charles, education is the most important thing to distill in his ward, but the children's authorities have other ideas about how a girl should be raised. Considering the novel is caused Rooftoppers, much of the book was given over to Sophie's life with Charles, so that I found myself missing Charles' peculiarities once Sophie took to the roofs.

This is Katherine Rundell's debut novel, so it can be forgiven that the balance between introduction and "rooftopping" did not seem quite right; especially since her prose style is so inviting and soothing, written like a classic children's fairytale with feisty modern characters and a dangerous path of adventure.

To see the rest of my Carnegie reviews, click here.

Liar & Spy

Rebecca Stead

London, Andersen, 2013, 180p

Last term, my colleague, Hannah from Oxford Youth Works, and I embarked on establishing a Girl's Book Club for Year 7. Now, we are making some of the boys happy by making a club exclusively for them, using Rebecca Stead's Liar & Spy as our book for discussion.

Georges is a funny, clever narrator. There is a lot going on in Georges' life when he moves into a new apartment and meets Safer, a skilled spy. Safer invites Georges to join his spy club, the main mission of which is to find out what is going on in the apartment of the mysterious Mr X. As time goes on, Safer becomes more demanding, and Georges starts to question if the friendship and the spy club are worth sacrificing his morals for.

Yes, the names of these characters are rather strange, but seeing as the whole story is delightfully uplifting, it doesn't really matter. And in some ways, the friendship between the boys is strengthened by their mutually unusual names.

Although the main plot focuses upon the spy club, Georges and Safer both have issues they are struggling with and unwilling to share. The club helps distract them from their hopes and fears, but also helps them process some of the challenges they are facing.

Georges is an adorable protagonist - I love Rebecca Stead's style and the voice she has created for our narrator. Not only is does the plot swiftly progress, but you learn little facts along the way as Georges describes his lessons at school and learns from Safer in spy club.

I cannot wait to see what my year 7 boys make of this novel!

To see the rest of my Carnegie reviews, click here.

All the Truth That's In Me

Julie Berry

Dorking, Templar, 2013, 266p

When Judith returns home, her tongue cut out and the last two years a mystery to all around her, she is outcast by her society and her family, subject to looks of horror and pity. As the town talks, there is only one person she wishes to listen to her - Lucas, the boy she has always loved.

Set in the early American settlements, All the Truth That's In Me is a haunting, dark novel about abduction and young sexuality. Judith is victimised by those in her town, who assume her kidnapping was of a sexual nature; and she is continuously haunted by the feeling that men only want her as a silent object. As the story unfolds, it becomes apparent that there is more mystery to Judith's story than the townsfolk have presumed.

The novel is told in first person by Judith, who often narrates as if she is speaking directly to Lucas, pleading for his sympathy and understanding. The chapters are very short - some only a sentence long - meaning reading is easy and swift.

I found myself quite caught up in the romance - Judith's longing is heartbreakingly beautiful, as she sits on the sidelines of Lucas' life. And she is a surprisingly strong protagonist, despite her many obstacles. She is brave and strong, fighting for justice and protecting the man she loves. If anything, Lucas seems weak in comparison.

I am finding this year's Carnegie list to be surprisingly dark, especially compared to the variety of the 2013 list - many of the books would not be typically suitable for teenage readers - yet I am enjoying the journey of shadowing.

To read more of my reviews of the 2014 Carnegie shortlist, click here.

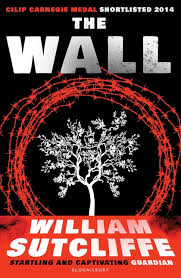

The Wall

William Sutcliffe

London, Bloomsbury, 2014, 286p

I have been very slow about making my way through the Carnegie shortlist this year, but have stepped up my game this half term with The Wall.

Joshua has lived alongside the wall for many years, with a vague awareness of what might be on the other side. One day, he discovers a tunnel that leads to the other side, a forbidden territory for people from his side of the wall. There, he finds terror, violence, and kindness, and his newfound knowledge changes his life forever.

The Wall is a dark, dangerous novel about segregation. Sutcliffe has created a ficitonal world losely based on the Israeli settlements on the West Bank, and he explores the issue of racial prejudice that is ingrained in this and so many other areas.

The journey of discovery that Joshua embarks upon is full of danger and pulls his already fragile family unit apart. Joshua's father passed away in a military incident relating to the wall, and his stepfather is a brute, angry force. Joshua tries to bridge the gap through helping those who showed him kindness, but is simply punished and rebuked by his family. Those on his side of the wall are protected from the dangers and repression, but what he sees when he discovers the tunnel can never be unseen.

To see the rest of my Carnegie reviews, click here.

In Darkness

Nick Lake

London, Bloomsbury, 2012, 333p

My Carnegie journey has come to an end with this brilliant story of tragedy and death. It has been a brilliant experience, but I am so glad I am not responsible for choosing a winner.

Simultaneously telling the story of a young boy trapped under the the rubble of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and the battle for liberation of the Haitian slaves under Toussaint L'Ouverture in the 18th century, In Darkness is a heart-breaking novel. I knew very little about the history of Haiti before reading this story, but now desire to know more. The story is about struggle against oppression, the fight for freedom and the desperation caused by imprisonment, both for black slaves under French rule, and young gangsters in the slums of Port-au-Prince.

Also, perhaps because I just read it, I saw some parallels between this story and Midwinterblood. Both authors explore the possibility of souls being able to survive throughout time, living through different bodies, seeing the world through different eyes. In Lake's story, both Toussaint and Shorty share the same soul, and in their dreams, they see the lives of others who have lived before and will live after them.

The story of the slave uprising is incredible, though Nick Lake admits he may have sugar-coated some of the events. Toussaint is an inspiring leader, preferring to maintain the land and spare the lives of the masters where possible. He doesn't want revenge, he just wants freedom; but death is a price that sometimes must be paid.

The young modern protagonist is an endearing character - misunderstood, scared, and desperately missing his twin sister, he joins the Route 9 gang in order to get revenge on the men who killed his father. He helps deal drugs and punish those who don't pay up. He admits he felt that rush when killing people, but you understand why - he has no money, no family, and little hope of escape from the slum. His best hope is to find a place within the street gangs. They respect him, and fear him; they believe he is blessed by the gods.

Vodou is a significant theme in this novel - both stories massively revolve around the belief in symbols, idols and magic. Men follow Toussaint because they believe he is possessed by the spirit of the lwa (deity) of war, and the gangstas trust Shorty because he is a twin and carries a pwen, a small stone containing the spirit of the lwa.

This novel is dark both metaphorically and literally, and the theme of imprisonment is recurrent. Trapped under the rubble after the Haitian earthquake, most of the story is told by a young boy trying to stay sane. He is imprisoned in his underground cave, like Toussaint is imprisoned by the laws of slavery and the racist assumptions of the white. The parallels between the lives of the two character, living over two hundred years apart, are full of darkness, sadness, and death. And yet, it is incredible how you forgive them both their wrong-doings, as you hear the story from their perspectives. Nick Lake makes you think about heroicism - he makes you question yourself and what you would do if you were them. Unfortunately, I fear many of us could never be so brave.

Midwinterblood

Marcus Sedgwick

London, Indigo, 2012, 263p

This is an incredibly dark, brilliantly Gothic novel. I have not read something so scary in some time, and I loved the feeling it gave me. Sedgwick defines the Gothic genre in it's modern form, and Midwinterblood is a fabulous example of his skill.

Written in reverse chronological order, this is a story of life, death, and love. It is set on Blessed Island, so far north the sun rarely sets. Mystery envelopes the island, as folk lore suggests that the people here never grow old, fueled by a unique healing plant, the Blessed Dragon Orchid. In 2073, journalist Eric Seven arrives there to learn more, but gets the feeling he has been there before.

It's really hard to write about this book without giving too much away, but let me just say that this novel contains several interlinked stories with recurring characters. It looks at the journey of two souls across many centuries, constantly searching for each other, wanting to be together.

That's the romantic aspect, but the part I loved the most was the Gothic themes. So far from the real world, Blessed Island is eery and mysterious - all is not as it seems. Characters keep popping up, they feel like they recognise each other, even though they cannot possibly have lived that long. Sedgwick plays with the idea of life eternal, both in the literal sense, with those characters who consume the Dragon Orchid, and in terms of eternal souls, with the souls of Eric and Merle finding each other throughout the centuries, despite the odds against them.

This novel took me back to the Gothic literature I studied at university - Poe, Hawthorne, Henry James. The suspense and drama are perfectly choreographed, taking the reader back in time, developing completely realistic worlds in each setting. Sometimes, I had to flick back through the pages to remember who was who, but I loved the slow revelation of the truth through the darkness of the story. At the end, everything came together, and all I want to do is read it again - I know it will reveal more to me with each re-reading.

Maggot Moon

Sally Gardner

London, Hot Key Books, 2012, 279p

What an unusual, original novel. Whereas The Weight of Water was unique in it's approach to story telling, Sally Gardner clearly has a brilliant imagination and had created a plot like no other.

Maggot Moon does not give much away until you are deep within it's pages - the cover and blurb say little about the plot, and the first few pages make it seem like a normal story of boyhood. Instead, it is about a strange dystopia in which people go missing without warning and the Motherland rules an oppressive regime.

Despite appearances, this is a very dark novel - it is like a world in which the Nazis won the Second World War. Power is held by a minority, and the weak struggle to rise up. Differences are eliminated, and conspiracy is ripe. The Motherland are attempting to launch a rocket to the moon, but the young protagonist Standish Treadwell is sure it it all lies.

The novel jumps about rather a lot, and as such, little is given away in the first few pages. Luckily, Gardner offers enough to make you want to keep on reading. In time, all is revealed. The pages are illustrated with gruesome images of rats and flies, adding to the sense of danger and decay that pervade through Standish's adventure. He is an unlikely hero, finding bravery in comradery. Against the power of the Motherland, Standish has companionship in the form of his subtly rebellious grandfather and the Lush family. Hector Lush becomes Standish's friend, his brother, and their relationship empowers Standish to be strong.

Sally Gardner has created a troubled, horrible world, but in it, she has given her reader hope and offered us faith in humanity. As in many novels about teenage characters, friendship can overcome adversity.

The Weight of Water

Sarah Crossan

London, Bloomsbury, 2013,

If the Carnegie prize is looking for originality, this book is a winner. Written in the form of a collection of poems, The Weight of Water tells the story of Kasienka, a school girl who moves from Poland with her mother to search for her absent father.

I was not expecting this collection to tell such a brilliant story. When I flicked through, I thought it was an anthology, but instead, it is almost like a novel in it's detail and care. The structure of the poems adds meaning to the plot, as the way the words fall on the page reflect the narrator's feelings.

Kasienka has a hard time of it at school. She is instantly recognised as different - she has the wrong rucksack and her hair is too short. When one of the boys tries to be nice to her, rumours start to spread. Meanwhile, Kasienka's mother searches ardently for her husband, unable or unwilling to move on. Mother and daughter start to drift apart, as Kasienka longs for home, and her mother longs for love.

Recently, I have been reading poetry written by the students at my school, many of whom have lived a life like Kasienka - displaced, fatherless, outside. The poems in The Weight of Water are beautifully written - so convincing that I had to check Sarah Crossan's biography because I was convinced these were written from experience. I'm learning to appreciate poetry as a method of story-telling, and Crossan's book is a brilliant example of this technique on a grand scale. This is such an incredibly unique way to tell a story, and I now want more of the same!

A Greyhound of a Girl

Roddy Doyle

London, Scholastic, 2012, 168p

I regret attempting to read this novel on a train. Public spaces are the worst places to cry. This beautiful story left me with emotionally wrought but strangely comforted.

A Greyhound of a Girl is about four generations of women dealing with death. Mary hates visiting the hospital, where her grandmother, Emer, is staying; until one day a ghostly stranger tells her to tell her grandmother that it is going to be okay. Together, the women help Emer deal with what is to come, as they look back on childhood memories and the challenges of motherhood.

Mary is a sweet little girl, full of sarcasm and intelligence. She a self-conscious ten-year-old, in that place between innocence and maturity, full of hope for the future and fear of losing her youth.

It is set on the east coat of Ireland, just south of Dublin, with a typically Irish family set up, as you would expect from Roddy Doyle. Having visited the area just last summer, I was disappointed that the novel lacked detailed descriptions of the surrounding scenery. Maybe it is too brilliant to put into words.

The novel would be a brilliant book to offer a young girl facing the challenges of a death in the family, as it dispels that fear of the unknown. It is slow-paced and gently emotional, written in fairly childlike language. The themes are heavy, but are presented with care and sensitivity - a brilliant Carnegie nominee.

Code Name Verity

Elizabeth Wein

London, Egmont, 2012, 441p

It's not often that you find a book about such heroic young women. Most World War fiction focuses upon men at war and women at home, but Code Name Verity drops two incredible young women into Nazi-occupied France, into situations so challenging I can hardly imagine how they managed.

In her epilogue, Elizabeth Wein is overt in stating her intentions for this novel. As a female pilot herself, she wanted to explore the possibilities for what she might have done during the Second World War. As you may imagine, female pilots were not common during the 1940s, but there were exceptions.

This is the story of two friends in a desperate situation. The novel opens with the diary of Verity, written in Nazi prison in France. She has been tortured, forced to reveal details about Allied aircraft and codes. She is bruised, emotionally damaged, and weak. She tells the story of how she came to be captured, having crash landed in France on a flight with her friend, Maddie. The second part of the novel is written by Maddie, separated from her friend and trying to find out where she is.

The characters are brilliant, their friendship is inspiring. In a world before technology, their friendship develops over several months, and under the challenge of being unable to talk about the secrets of their jobs.

At first, I was unsure about the intended audience for this novel, as the characters are grown up women. So many young adult and teenage novels are written about young characters that I was thrown off. But the author clearly avoids being too explicit about life in a Gestapo prison, hardly even hinting at sexual abuse or torture - the story is not to cause distress. The focus of the novel is about female friendship, and the bravery of young women who suppress their fears in order to help with the war effort.

This is another novel on the Carnegie shortlist for teenage readers. It is a fabulous read, inspiring young women and highlighting the possibilities available to them. However, I am concerned about it's chances to win, as the female-focus might not be of interest to boys.

A Boy and a Bear in a Boat

Dave Shelton

Oxford, David Fickling, 2012, 294p

Another Carnegie book, following on from Wonder. This one is of a slightly different style, being slightly less thought-provoking and emotional.

A Boy and a Bear in a Boat - the title kind of speaks for itself. A boy and a bear set off in a boat for a nondescript journey. When the bear asks, "Where to?", the boy replies, "Just over to the other side, please." Sounds simple enough, but the journey is wrought with anomalies in the tides and strange weather, so the least of my concern was why the bear could talk.

The novel was not full of twists and turns, but was a slow-paced, gentle sort of ride across the sea. Of course, things happened - sea creatures sneak up on them, they run out of food - but the story does not carry itself on the back of adventure. Even the characters are not greatly developed; we learn that the bear likes tea and the boy can be brave and can act the leader when needed, but we do not learn their names.

I kind of liked the pace and story-telling style of this book, but I am not sure that many kids would engage with it. The language was delightfully childish, and the novel was full of brilliant illustrations, awakening the reader's imagination with pictures of the stormy sea. In an ideal world, this kind of gentle romp would be all that a young reader would want or need; but I fear that, with the increasing demand for drama and instant gratification, this novel might not be what many young people want.

Wonder

R. J. Palacio

London, Random House, 2012, 313p

Some stories are told so well that you want them to be true. Over the next few weeks, I am embarking on a mission to get through the CILIP Carnegie Children's Book Award short list. I was in no doubt as to which I wanted to start with, having heard such incredible things about R. J. Palacio's novel, but I was still impressed.

Wonder is about a young boy with a facial deformity. August Pullman was born different but has always seen himself as ordinary. Yet his first day at school, having been educated at home, is full of apprehension. The novel is touching and heart-warming - the kind of book that makes you feel incredibly lucky to be you, whoever you are.

I read this novel in about six hours, on and off. It has been a while since I read something that fast! But August is a beautiful character. He does not look like the other kids at school, but Palacio has not made him some sort of angel child. He is normal. He wants to fit in. He struggles, because people carry many misconceptions about him, and some people are mean. But he doesn't hate those who point and stare; he just wants them to understand that he is just like them.

And that is what this novel allows. Written from the point of view of several narrators, the novel is not preoccupied with a boy who feels sorry for himself, but with explaining what life is like for August and those around him. First, it delves into the mind of August, a surprisingly understanding and brave young man. Then, his older sister recounts growing up in second place, always having to make sacrifices, but knowing that they are worth it, because she loves her brother. From the point of view of his friends, we learn what it feels like when you first see August; the moment of shock quickly followed by a feeling of guilt. But soon they know August for who he is, not what he looks like.

This novel tells us it is okay when you don't understand something. Palacio gives the reader the opportunity to see the world through another's eyes - through several sets of eyes. It shows us that no one is perfect; everyone feels angry or jealous or lonely. But within us is the ability to be kind:

"...always try to be a little kinder than is necessary." - J. M. Barrie

The Graveyard Book

Neil Gaiman

London, Bloomsbury, 2008, 289p

So it had to be done. I had to write a entry about The Graveyard Book.

Full disclosure: I am a little bit in love with Neil Gaiman. Not only does he write great fiction, but he's a lover of libraries! Double win.

The Graveyard Book is about the life of Nobody Owens (aka Bod, a name that a friend of mine is hoping to use for her children, somehow), who is adopted by ghosts and raised in a graveyard. He learns about life through his interactions with the dead - they teach him history and maths, as well as survival lessons and the difference between right and wrong.

I wasn't sure what to expect with this book. As I have already confessed, I do love Gothic fiction; but when I was a teen, I never read stuff like this. I'm more into Gothic fiction set in the past - the Victorian era, the Enlightenment - with the context of change and upheaval.

Yet, Gaiman pulls it off. I was terrified of The Man Jack, and I had nightmares about the Ghouls.

I loved all the little details, like the Freedom of the Graveyard. I also enjoyed the little morality lessons that were in there, like when Bod comes up against some bullies at school.

But most of all, I felt that Gaiman's characters were incredible. I enjoy the comic relief provided by the inhabitants of the graveyard, and the companionship that comes from Scarlett and Elizabeth. He hit the nail on the head with Bod, creating a normal growing boy, but within the most unusual of settings. It's said of Bod that, "He looks like nobody but himself", but I'd argue he is like everybody - he is so easy to relate to. My favourite, of course, was Silas. Who doesn't want someone like Silas to watch over them. He reminded me of Sirius Black - reserved, cautious, but full of love.

So, if I haven't already made it clear - I recommend The Graveyard Book.