Insurgent

Veronica Roth

London, HarperCollins, 2012, 525p

Insurgent

Veronica Roth

London, HarperCollins, 2012, 525p

Good and evil are never as clearly defined as they first seem. Divergent convinced me that the Dauntless were the best of the factions - the brave and noble warrior types - but Insurgent shows that their aggression comes at a cost, and perhaps we all need a little of every faction to be balanced individuals.

Following the devastation inflicted by the Erudite at the end of the last novel, Tris and the Dauntless find themselves lost and divided - some have allied with the information-hungry Erudite whilst others have gone into hiding, taking refuge with the kind Amity faction. The Amity are reluctant to take sides, but are put in a difficult situation when threatened by the Erudite, knowing full well they are in a dependent situation.

The Dauntless traitors continue to spread the Erudite simulation serum through the other factions, preparing an army of mindless drones. Tris suspects there might be more to the Erudite mission than power - old Abnegation leaders have implied that the Erudite are keeping a secret and that all the factions deserve to know the truth.

Throughout Insurgent, Tris battles with depression - she feels like she has lost everyone she loves and is haunted by guilt over what she did during the heat of battle. Try as he might, Tobias cannot seem to do the right thing, and Tris finds herself building up walls and keeping secrets. Tris could have easily become an annoying, moany character in this novel, but Veronica Roth is a talented and engaging writer who maintains the reader's sympathy during the hardest of times.

I absolutely devoured this book - I was impressed to find that it can be added to that short list of brilliant sequels along with Toy Story 2 and the second Godfather movie. Now the characters are well developed and the direction seems clear, the novel flows at a fast pace, with drama at every turn, and with a complete disregard for conventional the good vs evil dichotomy. Nothing is as it seems.

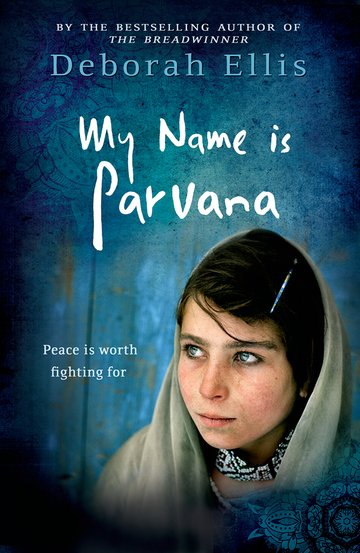

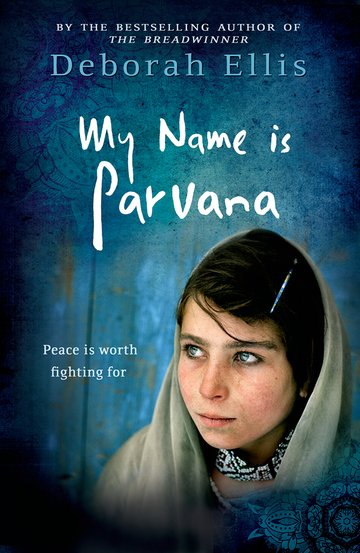

My Name is Parvana

Deborah Ellis

Oxford, OUP, 2014, 240p

Sometimes, stories can be very difficult to read, especially those based in fact. Deborah Ellis carries out thorough research before writing, visiting refugee camps across Russia and Pakistan to hear the stories of people just like her protagonist, Parvana.

Parvana is being held captive by the American army in Afghanistan, and is refusing to talk. She is accused of bombing her own school, which was run by her mother and run for the education of local girls. Parvana is a well-educated, intelligent young girl, but the American army simply see her as another threat. The novel jumps back and forth between Parvana's imprisonment and her time at school, explaining how she has been mistaken for a terrorist.

My Name is Parvana follows on from previous novels by Deborah Ellis, including The Breadwinner. These previous stories told of Parvana's journey as a refugee, but now she has a home and a purpose. Yet, not everyone sees the education of women as a positive, empowering force for good. Parvana and her family are threatened and feared, and have a lot of work to do to prove their value.

I enjoyed reading this novel because the language was accessible and the characters were likeable. I like that it jumped back and forth between past and present, meaning there was constanly something happening. I was not hugely gripped by the story, but I cannot articulate why.

My Name is Parvana

Deborah Ellis

Oxford, OUP, 2014, 240p

Sometimes, stories can be very difficult to read, especially those based in fact. Deborah Ellis carries out thorough research before writing, visiting refugee camps across Russia and Pakistan to hear the stories of people just like her protagonist, Parvana.

Parvana is being held captive by the American army in Afghanistan, and is refusing to talk. She is accused of bombing her own school, which was run by her mother and run for the education of local girls. Parvana is a well-educated, intelligent young girl, but the American army simply see her as another threat. The novel jumps back and forth between Parvana's imprisonment and her time at school, explaining how she has been mistaken for a terrorist.

My Name is Parvana follows on from previous novels by Deborah Ellis, including The Breadwinner. These previous stories told of Parvana's journey as a refugee, but now she has a home and a purpose. Yet, not everyone sees the education of women as a positive, empowering force for good. Parvana and her family are threatened and feared, and have a lot of work to do to prove their value.

I enjoyed reading this novel because the language was accessible and the characters were likeable. I like that it jumped back and forth between past and present, meaning there was constanly something happening. I was not hugely gripped by the story, but I cannot articulate why.

Especially seeing as Parvana is such an inspirational protagonist: brave and self-assured, despite all she is up against. Her story is harrowing but honest. Ellis is not writing to evoke emotion - this story is no tear-jerker - but writes to inform. Her novels are topical and relevant, making real an experience that is unimaginable for many of her readers.

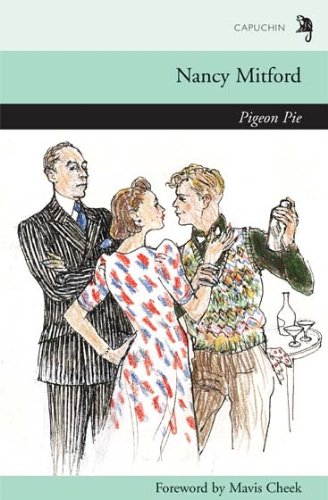

Pigeon Pie

Nancy Mitford

London, Capuchin, 2012, 159p

Last year, my mother read an extended biography of the Mitford sisters, and regularly updated me on the information she has learned about the family of socialites. I was intrigued, so when I stumbled upon a novel by one of that multitude, I thought it might be time I learned more.

Sophia Garfield is a sophisticated young woman of the upper class at the outbreak of the Second World War. She lives with her husband, with whom she has a marvelous arrangement that involves Sophia having a lover and he entertaining a woman who comes across as a religious lunatic. When she accidentally stumbles upon a secret within her house, Sophia is enlisted as a spy, and finds herself torn between the desire to show off to her friends and an uncertainty about who she can trust.

I knew I'd love Pigeon Pie from the opening line - it is witty, intelligent, and sharp. Although Nancy lived the high life, she clearly found it very entertaining and uses the upper classes as great fuel from which to be inspired. In part, you can see her own experiences in the novel, as she laughs at the ridiculousness of those Brits who supported the Nazi. She mocks the selfishness and naivety of those who sit in the Ritz and drink tea whilst discussing politics, when they seem to be so oblivious of what is really taking place in Germany.

The whole novel feels a little like a farce, with Sophia's strange domestic set up, the way she trips and falls into a career in espionage, and the coming and going of her friends in parliament. And yet, beneath the comedy is a serious commentary on national socialism and the outbreak of war in 1939.

The whole novel feels a little like a farce, with Sophia's strange domestic set up, the way she trips and falls into a career in espionage, and the coming and going of her friends in parliament. And yet, beneath the comedy is a serious commentary on national socialism and the outbreak of war in 1939.

When the Guns Fall Silent

James Riordan

Oxford, OUP, 2013, 153p

The events of Christmas Day in 1914 is the stuff of legends. It is written about, adapted for television, and heralded as one of the great symbols of humanity.

When the Guns Fall Silent is another account of this day. When veteran Jack takes his grandson to see the graves in France, he finds the grave of one of his friends has been recently visited. Upon the memorial sits a picture of a group of young men on Christmas Day in 1914, Brits and Germans together on that unique day. Jack sees a face he recognises, and visions of the war return to him.

This novel recounts how Jack ended up on the front line, even though he was too young to be there. When war breaks out and young men join the army, Jack and his friend Harry are recruited to the Portsmouth FC first team. Part of their commitment involves training with the military reserves, and the boys soon find themselves beaten down and remoulded into soldiers. Taking pride in their new-found heroism, they sign up and are shipped to France, where the horrors of war are like nothing they could have imagined.

Then, on Christmas Day, a German soldier plants a Christmas tree, and soon the two sides have agreed a temporary ceasefire. It is almost unimaginable that they can go back to killing one another the next day.

The trenches have become such a vivid image in the minds of the public that Riordan does not need to waste time describing the grime and horror, but instead can concentrate on the development of Jack and his German comrades. He also fills the book with facts about the war - little snippets of information about the suffrage movement and war propaganda disguised as fictional elements of the story.

When the Guns Fall Silent is a touching, beautifully written story; perfectly timed for republication this year.

A Farewell to Arms

Ernest Hemingway

London, Arrow Books, 2004, 293p

This is a rather delayed write up, considering I actually read this novel about a month ago for the second of our staff book club meetings - a lovely gathering to discuss Hemingway. Last time, we realised that none amongst us had read the American great before, so we set out to rectify this!

Frederic Henry is an American ambulance driver for the Italian army during World War One. On a simple level, A Farewell to Arms is about Henry's love affair with an English nurse, Catherine Barkley; but that is only one small part of this novel. It is a vivid story about conflict, masculinity and the beauty of Italy.

Having read so much children's literature recently, Hemingway's prose was initially somewhat hard to get into; but as I read on, I found myself engrossed in the long, descriptive passages and the conversational style. What I particularly enjoyed was the fact that he did not indicate who was talking in sections of dialogue, leaving it up to you to work out who was saying what. As I got to know the characters better I could work out who was talking by their style of speech and the voices I had created for them in my mind.

This is not a particularly action-packed novel. Sometimes, when people were killed, it took a moment for me to realise because nothing was written literally. The realities of war felt distant from the protagonists, as if they could protect themselves by blocking out the death and devastation around them.

In terms of the plotting, this novel is a perfect model of realist writing - opening a window into the life of a soldier, viewing for a short while, and then closing. More modern fiction tends to be preoccupied with the psychology of the characters, embedding flash backs to contextualise their childhood. I found myself wondering how Henry had ended up in Italy, and Hemingway never satisfied my curiosity, but I really appreciate this. Instead, A Farewell to Arms presented me with a perfect snippet of the lives of Frederic and Catherine.

Stories of World War One

ed. Tony Bradman

London, Orchard, 2014, 304p

Memorials to the First World War will come in many forms this year, but Tony Bradman is one of the greatest editors of short stories today. This collection has vast variety and a great selection of authors to read.

My favourite story was The Men Who Wouldn't Sleep by Tim Bowler, which is about a young boy who volunteers at a hospital for returning soldiers. There, Robbie meets Bert and Jimmy, two injured soldiers. Bert is incredibly protective of Jimmy, who sits in a trance like state, unable or unwilling to talk to anyone. Robbie is assigned to sit and talk with Jimmy - at first, he struggles to know what to say, but soon he finds himself sharing his worries about his father, who is lost in France. It is a touching, tragic story; one of many in this collection that stay with you long after you have finished reading.

There are stories set on the home front and on the front line, in France, England, Ireland and elsewhere. Some are about the young and others are about older soldiers. Each of the authors tackles a different element of war, such as the separation of childhood sweethearts, mothers' fears about their sons, and young boys in the trenches. There is a brilliant contribution from Children's Laureate, Malorie Blackman, which explores the relationship between two half brothers on the front line, torn between their love for each other and masculine pride.

Although I didn't feel that the collection began with a particularly strong story, I liked the way these stories brought the war into the present, making it accessible for modern teenage readers. There is a story for everyone in this book, though you may have to read them all to find the one for you.

Stay Where You Are and Then Leave

John Boyne

London, Random House, 2013, 247p

I love the way John Boyne writes - it is so poetical and descriptive that you become completely lost in his world. His novels are so emotional, taking you on a journey of love, loss and hope.

Alfie's fifth birthday is overshadowed by the outbreak of the First World War. At the last minute, most of his friends find they cannot come to his party, caught up in their own family concerns. And those who do attend are distracted by the impending stress and fear of war. The next morning, Alfie's father volunteers, convinved it will be over by Christmas. But four years later, he still isn't home and his letters have stopped coming.

Although his mother tells him his father is away on a special secret mission, Alfie is convinced his father is dead. Until one day, shining shoes in Kings Cross station, he accidentally reads the papers of a doctor and discovers his father is actually in a hospital in Ipswitch. He sets out to bring him home, but finds himself totally unprepared for the impact the war has had on the mind of his father.

John Boyne is the kind of writer who manages to make you completely adore a character before putting them in a situation of drama and heart ache. Stay Where You Are and Then Leave is slow paced in the early chapters, setting a scene of wartime poverty and family separation. Alfie is a fundamentally good young boy - perhaps a little idealised in contrast to many teenage protagonists of today - but he is determined to go about his secret mission alone rather than asking his mother or neighbours for help and advise, which innevitably cannot end as well as he hopes. So as the reader, you watch helplessly as Alfie stumbles into territory from which you are convinced will only end in tears.

Today, we have a much better understanding of shell shock than doctors had in the early twentieth century. We can empathise with the distress of battle and the struggle faced by soldiers returning to everyday life. But people continue to suffer from the psychological effects of warfare, and not all families are as lucky as Alfie's.

Stay Where You Are and Then Leave

John Boyne

London, Random House, 2013, 247p

I love the way John Boyne writes - it is so poetical and descriptive that you become completely lost in his world. His novels are so emotional, taking you on a journey of love, loss and hope.

Alfie's fifth birthday is overshadowed by the outbreak of the First World War. At the last minute, most of his friends find they cannot come to his party, caught up in their own family concerns. And those who do attend are distracted by the impending stress and fear of war. The next morning, Alfie's father volunteers, convinved it will be over by Christmas. But four years later, he still isn't home and his letters have stopped coming.

Although his mother tells him his father is away on a special secret mission, Alfie is convinced his father is dead. Until one day, shining shoes in Kings Cross station, he accidentally reads the papers of a doctor and discovers his father is actually in a hospital in Ipswitch. He sets out to bring him home, but finds himself totally unprepared for the impact the war has had on the mind of his father.

John Boyne is the kind of writer who manages to make you completely adore a character before putting them in a situation of drama and heart ache. Stay Where You Are and Then Leave is slow paced in the early chapters, setting a scene of wartime poverty and family separation. Alfie is a fundamentally good young boy - perhaps a little idealised in contrast to many teenage protagonists of today - but he is determined to go about his secret mission alone rather than asking his mother or neighbours for help and advise, which innevitably cannot end as well as he hopes. So as the reader, you watch helplessly as Alfie stumbles into territory from which you are convinced will only end in tears.

Today, we have a much better understanding of shell shock than doctors had in the early twentieth century. We can empathise with the distress of battle and the struggle faced by soldiers returning to everyday life. But people continue to suffer from the psychological effects of warfare, and not all families are as lucky as Alfie's.

Stormclouds

Brian Gallagher

Dublin, O'Brien, 2013, 218p

I don't know a lot about the conflict in Ireland over the last fifty years, and am always surprised at the lack of teaching of this subject. Fortunately, we librarians can always count on engaging and fact-based fiction to teach teenagers a little about the things they don't learn in the classroom.

In the 1960's, conflict between the loyalists and nationalists is rife. Emma and Dylan move to Belfast because their father, a journalist, has been sent there to report on current events. They are sociable and outgoing kids, so unsurprisingly make friends quickly. Emma meets Maeve at her running club, while Dylan meets Sammy at football. When the siblings bring their new friends together, they find that both have deep-seated suspicions about each other: Maeve is from a Catholic nationalist background, whereas Sammy is a Protestant unionist. With time, they begin to realise that they aren't that different after all; but the rest of Belfast are not so quick to change their views, and conflict breaks out across the city.

Stormclouds has a clever moral message about prejudice and difference: the children put the adults to shame with their ability to see past religion and politics. The brash aggressiveness that leads to street warfare is distressing, especially when contrasted to the friends' open mindedness and love for one another. This is a brilliant, gripping book, teaching it's young audience about an important and ongoing political conflict.

Othello

William Shakespeare

c. 1604

My sixth formers are currently studying Othello, and I am ashamed to say that it is one of the few plays of Shakespeare I have not read. I barely even knew anything about the plot, so I set out to rectify this.

The play begins with a conversation between Iago and Rodrigo, two courtiers who are discussing the Moor, Othello. During the first scene, they do not state who they are talking about, instead referring to the soldier in racial slurs such as "an old black ram". The two men are outraged that Othello has secretly married Desdemona, jealous and angry at the rising social status of their colleague and rival.

Iago is driven by viscious resentment, and sets out to destroy the Moor. He plots behind the backs of his fellow courtiers, whispering false secrets in their ears, tricking them into believing the worst in others. He convinces Othello that Desdemona has been unfaithful to him with Cassio, and drives Othello to committing the most evil of crimes against his once beloved wife.

It's classic Shakespearean tragedy - a dangerous romance that transforms social barriers and parental expectations; a jealous subordinate, unhappy with his own lot and pent on revenge; proud men who are fooled by their inferiors and seem unable to talk rationally with their wives; and a drunken fight scene.

But best of all, the students at my school love it! With many of them being from Muslim families, they fully understand the challenge of racial differences and the value of chastity and virginity. Othello is a surprisingly modern text, remaining relevant with students for whom an honour killing can be a reality. Once they have gotten a grasp of the language of the fifteenth century, the tragedy and drama grips them - I don't think I have met a group of teenagers so excited by Shakespeare.

What Are We Fighting For?

Brian Moses and Roger Stevens

London, Macmillan, 2014, 112p

Seeing as this year marks the centenary of The Great War, I am anticipating many publications to deal with this subject. What Are We Fighting For is the first I have come across: a varied, original collection of poems written and collated by Brian Moses and Roger Stevens.

At first, I thought this collection would be an anthology of existing poems, and was disappointed to find that it was in fact some new poems written by contemporary poets. I felt a little concerned that they had no authority on the subject and that the writing would be idealised or exaggerated.

But I was pleasantly surprised to find poetry that covered a variety of subjects in a factual and informative way. The collection felt a little like a history book, giving information about life in the trenches, the causes of conflict, and what things were like for those people left at home. Some of the poems are supported with snippets of factual information, explaining what realities the stories relate to. And each poem is just that - a little story about a person or a place or an event, taken from history and embelleshed in a more accessible manner.

This book contains poems about all conflict - from the First and Second World War, right through to modern day conflicts. The final section seems more childlike and innocent, exploring the world through the eyes of young characters who do not see war in their back garden, but are sometimes vaguely aware of world news and battles fought overseas. There is even a poem about a playground fight, as Moses and Stevens cast doubt on conflict at all levels.

So despite not meeting my initial expectations, I found this collection of new poems to be touching, leaving the reader with food for thought; though I expect there to be a lot more high quality writing on this subject to be revealed over the next few years.

1602

Neil Gaiman, Andy Kubert & Richard Isanove

Marvel, 2011

I have been looking forward to reading this for months, so when I found myself with a quiet weekend, I indulged in a bit of Marvel gone historic.

It's 1602 and Queen Elizabeth is close to death. In her court, Doctor Stephen Strange and Sir Nicholas Fury conspire with the Queen to protect her, concerned that her death might bring forth the rule of King James, who has no love for magical arts. Witch-like activitiesn will be supressed and a reign of Catholicism will rule over England.

This gripping Gothic graphic takes all our favourite Marvel heroes back in time. From the X-Men to Fantastic Four to Captain America, they are all hidden under historical guises, unaware that they are about four hundred years too early. Something unexplained has disturbed the chronology of history, and somehow these characters have langed in Elizabethan England, unaware that they are destined for another time.

It is incredible how easily the Marvel characters slip into the seventeenth century - you might think that there would be profound differences in their situation, but actually it turned out to be rather easy to surplant them in another time. As in the twenty-first century, they are at risk of prosecution for their abilities, forced into hiding and always in conflict. Scientific explanations for their powers are replaced by magical and supersticious explanations, but the core 'otherness' remains.

There are many layers to this story, but the brilliant and detailed illustrations keep you abreast of the flow, and so it is able to jump around from each characters' storyline until they all come together to overcome the darkness that hangs over the world. For some of the characters, it is clear who their modern alter-ego is, but some are more subtle, revealing themselves to you as you read on and learn more.

I found myself completely engrossed in this story. If anyone has any doubts over the educational potential of graphic novels, surely this overcomes any argument against, as it teaches seventeenth century history through the medium of the superhero story.

Sweet Tooth

Ian McEwan

London, Vintage, 2012, 370p

Due to high demand amongst staff at my school, a colleague and I are establishing a staff book club, starting with Ian McEwan's Sweet Tooth.

Although McEwan has a tendency to be incredibly tough on his protagonists, I like his writing. He is gritty, getting right into the minds of his characters. They are not flawless objects you cannot believe in, but detailed and flawed individuals who often cause their own demise.

Serena Frome is no exception. She is an attractive, intelligent young woman, fresh out of Cambridge, when she is spotted by MI5. She is recruited for operation Sweet Tooth, a project to mould the face of British culture through supporting writers who reflect the government's desired national mood. It is 1972 and society is in a difficult place, with the Provisional IRA threatening terrorism, workers going on strike, and the Cold War hanging over Europe. Serena is told to manage Tom Haley, an English professor who has shown an aptitude for writing what MI5 want to see. She admires his work, and when she meets him, falls for the man himself.

This novel did not unfold in the manner I had expected. The blurb is enough to make you anticipate fast-paced action, but the drama occurs in a rather more leisurely manner. The reader is aware that Serena is doomed from the beginning, unable to tell Tom who she really works for. The secret builds between them as they become closer and closer, threatening to unravel their peaceful seaside idyll.

And yet, I hugely sympathised with Serena. It might have been her unadulterated love of reading or her misguided approach to romance, but despite her being incredibly different from me, I related to her feelings. This is where I think McEwan is highly skilled: he gets right into the subconscious of his characters, breaking down their motives and movements so that the reader becomes in tune with the protagonist, and you start to believe you might have acted exactly as they did.

I am really looking forward to discussing this novel with my colleagues and friends - even if we conflict, I love exploring a novel through someone else's eyes.

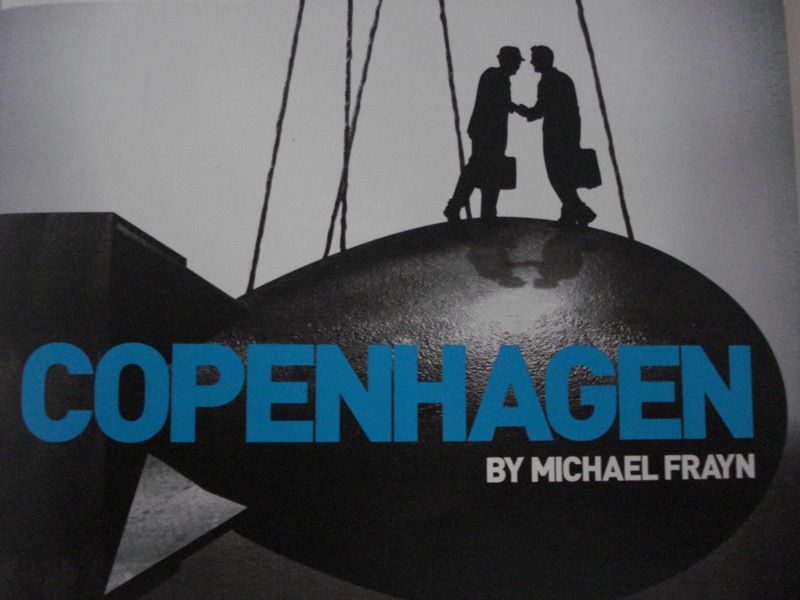

Copenhagen

Michael Frayn

I have to admit - I am still a little baffled by this play, just as I was when I read Spies.

Copenhagen is a fact-based play about a meeting between Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg in 1941. It is non-linear, jumping between the first time the men worked together in the 1920, their meeting in 1941 and an unspecified later date. The men discuss the creation of atomic weapons, trying to piece together the sequence of events of their historic meeting in Copenhagen in 1941.

Heisenberg and Bohr conflict

over what they remember from that fateful meeting in 1941. Neither

recalls exactly what was said or what was intended - as explored in

Spies, memory is never perfect.

The play is incredibly complex, both in terms of it's style and content. There are minimal stage directions and only three characters - Heisenberg, Bohr, and his wife Margrethe. All three remain on stage throughout, though sometimes the dialogue implies that the character talking might not be aware of the presence of others. This lack of formal structure means that the script has a lot of room in which the actors can play, presumably producing incredible theatrical shows. I think that seeing this on stage would definitely clear up some of my confusion.

Because the story is about science behind the atomic bomb, some of the language is incredibly jargonised. Much of the terminology was too difficult for me to understand, but beneath the physics was an exploration of memory and morality.

Undoubtedly, Michael Frayn is an incredibly well-educated writer, repeatedly exploring the flawed nature of memory and the significance of history. But this play was difficult to visualise - a stark contrast from other plays I have read recently in which stage directions bring to life the author's vision.

Any Human Heart

William Boyd

London, Penguin, 2009, 490p

It's quite nice to read a 'grown-up' novel for once. Any Human Heart contains the diaries of the fictional Logan Mountstuart, detailing his life across the twentieth century, incorporating real events and people. At different times, Logan is a writer, a spy or an art dealer; he lives in London, Paris, New York and Africa; he experiences the hardship of the Second World War, the swing of the sixties, and the simple peace of family life. I was utterly engrossed.

The diaries begin during Logan's school years, boarding in Norfolk, and travel with him all over the world. They are sporadic and often undated, with gaps filled by an omniscient, anonymous narrator. In places, there will be a gap of many years, but then they pick up again for no apparent reason. His entries vary in detail and tone, sometimes philosophical, sometimes bluntly matter of fact, but always honest. Being a well-educated writer, Logan's vocabulary is sophisticated and complex, with many words that I had to look up, but I loved the challenging nature of the novel.

It is a magnificent account of life, true in it's everyday occurrences and extraordinary moments. As Logan states:

"Isn't this how life turns out, more often than not? It refuses to conform to your needs - the narrative needs that you feel are essential to give rough shape to your time on this earth."

Logan's life is not without drama, but it also has great sections in which nothing much happens. And yet you get drawn into the details, from the days spent hobnobbing with literary greats to the end of year reviews in which he always declares he must cut down on alcohol.

What I admire most about this novel is the historical accuracy. There were episodes I read that seemed to be great works of literary fiction, but turned out to have actually occurred. Logan mixes with Hemingway and Virginia Woolf in the 1930's London - his fictional adventures pass cross their real lives. Later, he works for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, becoming embroiled in a murder scandal that later sees him imprisoned in Switzerland under mysterious circumstances. I was so in awe of Boyd's detailed knowledge of the twentieth century, to the point where I started to believe the fictional characters in the novel must also be real.

Any Human Heart was a pleasure to read. It is a gift to history and literature.

How I Live Now

Meg Rosoff

London, Penguin, 2004, 211p

Somehow, miraculously, I managed to avoid seeing the trailer for the adaptation for this novel before I read the book. But as such, I had no idea what I was about to read - whatever I had expected, this was not it.

Daisy is shipped by her father from New York to rural England in the hope that it will help her get better. She is an angry, lonely teenager suffering from anorexia. For the first few months, she finally starts to feel like she can be at peace here with her cousins; until war breaks out and the teenagers are separated, left to fight for survival in a world gone mad.

I thought How I Live Now was going to be a teen romance - the blurb on my version is very ambiguous, with no mention of devastating war. Whilst in England, Daisy falls for her mysterious cousin, Edmond. She admits it might be incestuous, but when war breaks out, you forget all about the romance plot as the characters are suddenly thrust into your worst nightmare.

The cause of the war is never fully clear - it is the perfect dystopia. As such, you are not preoccupied with the 'why' but focused upon the 'what'. The war is unpredictable and unexplained - no one ever seems sure of what is happening. For most of the novel, Daisy and Piper, separated from the boys, are left to fend for themselves, traipsing across the English countryside. It is picturesque and terrifying in equal measure - even if you do not live in England, you have some idea of what the countryside would be like, and here Rosoff transforms it into a vast, empty space with no refuge.

Food is a significant trope throughout the novel. At first, Daisy is distracted by her need to control what she eats, venting her frustration through her eating disorder. But when faced with the possibility of being unable to find food, the war forces her to eat all she can. Whole chapters of the novel are dedicated to Daisy describing the food she finds and cooks, whilst she craves toast and butter. This is very effective - food is something we can all relate to, and by focusing Daisy's suffering on such a universal concept, the war becomes real.

Even under the protection of adults, Daisy and her cousins are never safe. Throughout the novel, there is a massive disconnect between adults and children, but not in a Lord of the Flies sort of way. Instead, adults in How I Live now are completely null and void. These teenagers seem to survive better without adult supervision. Adults cannot provide answers or safety - if anything, they are the cause of all that is bad, being responsible for the war, for death and for the teenagers' separation and loss. Refreshingly, Rosoff does not patronise her protagonists - adults are not brought in to save the day - but instead shows the teenagers as the real heroes, with their love for each other overcoming all. In this way, this novel is a rare gem in which young people are truly of the greatest value.

Noble Conflict

Malorie Blackman

London, Random House, 2013, 357p

Words fail me when I try to describe how much I adore this novel. Malorie Blackman is best known for her Noughts and Crosses series, but this novel is what truly shows how talented and engaging she is.

Kaspar is a Guardian of the Alliance. His job is to defend civilians from Insurgents, the dangerous enemy intent on disrupting the peace of his society. Years ago, the Insurgents damaged the earth through experimentation, forcing the Alliance to segregate them. Now, the Insurgents are a constant threat, and the Alliance must fight defend, but aim to avoid causing any death.

But Kaspar starts to question what he has always believed to be true. With the aid of Mac, a kick-ass librarian, he delves deeper into the history of the Alliance and the integrity of some of the recent attacks, revealing some disturbing information.

Noble Conflict is an intelligent, thrilling read. Blackman does not patronise her reader, but challenges you to keep up with her. Her dystopia is complicated and thought-provoking - like Kaspar, I found myself stating to question what I knew about the society in which I live.

The action throughout this novel is brilliantly controlled and executed. From page one, you are gripped, as the Insurgents attack an Alliance ceremony. Each moment reveals a little more of the mystery to you, and you cannot help but read on! I can't pretend that I didn't guess the ending before it happened (I tend to do that a lot), but it made no dent in my enjoyment of the story.

Most of all, I love the characters in this novel. Kaspar is a dream protagonist - loyal, handsome, clever and a brilliant fighter. He has great friends, each of whom seem incredibly real and wonderful despite not being a significant element in the novel. But best of all are the female leads - Rhea and Mac. You barely get to know Rhea - she is doused in mystery, temptingly dangled in front of you and never fully revealing herself - but she is brave and feisty and passionate, providing Kaspar with the motivation to discover the truth. Meanwhile, Mac provides him with the resources to learn more. As a librarian, she is a credit to our trade. She never falters, she's smart, confident and driven; she is a perfect counterpart to balance Kaspar's fiery masculinity. And the tools she has to carry out research are genius - I wish I had little bots I could program to trawl cyberspace for information.

Plus, she gets the best line of the whole novel:

"Books and knowledge don't make for a safe world. Just the opposite. Books and knowledge are facets of truth and the truth can be very dangerous."

It is not completely clear if Blackman has a sequel in mind for this one, but I would love to read more about this world!

The Things We Did For Love

Natasha Farrant

London, Faber, 2012, 224p

The climax of this book was one of the most heart-breaking pieces of literature I have ever had to read. Based on true events during the Second World War, The Things We Did For Love unexpectedly transformed from a sweet love story to a tragic tale of brute violence.

Ari and Luc are sweethearts living in a small village in France during the Nazi occupation. Luc is unsettled, angry at what is going on around him, as minorities and rebels are being turned over to the Germans. He thinks he might be able to help if he joins the Resistance. But Ari fears he will only get hurt, and is convinced that their love can overcome his desire to leave.

The romance was not my favourite part of this novel - I am not a fan of the 'love overcomes all' plot where people sacrifice their beliefs for their lover. Luc was a passionate hero, guided by his morals and willing to give up his life for the cause. But Ari was a draining heroine - I felt like she was holding him back.

But it was not these two characters who make this novel great; instead it was the supporting cast. Ari's cousin, Solange, and her brother, Paul; Romy, the boy who has loved Ari for as long as he can remember, trying to do right by her; and the German officers, sent to commit the worst of atrocities and always carrying the weight of self-doubt and guilt.

Most powerful of all was the ending of this novel. Farrant writes in her afterword that this story is based on true events: on 10th june 1944, the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich entered the village of Oradour-sur-Glane and massacred it's occupants. Innocent men, women and children were slaughtered in the most horrifying of circumstances. Today, the town remains empty, haunted by it's tragic past.

Whether you like historical fiction or teenage romance, this novel has a beautifully dark story to tell, one that will make you ponder long after you have finished the final page.

War Horse

Adapted by Nick Stafford

(Michael Morpurgo)

Oxford Playscripts

Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2007, 127p

Last Thursday, I went with 100 year seven students to see War Horse in London. It was chaos, but that is another story - this blog is for reviews; and on my return from the theatre, I read the play.

I have already reviewed the Michael Morpurgo original here, so will not repeat the story - anyway, it is pretty well known by now. However, it was very interesting to read the play just after seeing it performed, as it shed light on some of the concepts for the creation of the story on the stage.

The play differs slightly from the novel - mainly in terms of the fact that the story is not told from the point of view of Joey, but from an omniscient perspective where multiple characters' stories are told. Nevertheless, Joeys feelings are expressed through his actions. For example, his early fear of people is shown through Joey's unwillingness to approach Arthur and through Arthur's one-sided conversations with the horse. In scenes where the animals are without humans, the action is described through stage directions, specifically designed to give the horses a emotive and quasi-human quality.

On stage, Joey's character is performed by three expert puppeteers, who manipulate the movements of the animal to the point where you forget it isn't real. The story is full of drama and action, with much of it taking place on battlefields. Joey becomes a symbol for all that was fought for during World War One, when parents were separated from their children, lovers were separated from their sweethearts. Arthur's search for his horse becomes a symbol for humanity and love, and Joey brings all sorts of people together - Germans, French and British.

The play is beautifully written, with incredibly evocative language. There was also brilliant use of other dialects (with translations) where the French and German characters were in scene. In particular, I love the monologues where Arthur talks to his horse, making promises to be together forever - this friendship is at the heart of the story and is what stays with most people long after they have finished reading.

Soldier Dog

Sam Angus

London, Macmillan, 2012, 275p

I have found this to be one of the most popular novels on this years Bookbuzz list - across the year 7s, both boys and girls love it.

Soldier Dog, on a most simple level, is War Horse with a dog. Our year 7s are currently involved in a cross-curricular project based around War Horse, with a trip to see the stage show later in the term, and many of the students have seen this similarity in reading the blurb and the first couple of pages of the novel.

However, unlike Morpurgo's acclaimed novel, this is not written from the point of view of the animal involved. Stanley is a fourteen year old boy who loves animals, particularly dogs. His brother is in France, so when his angry, neglectful father turns on him, Stanley decides to run away. He is underage, but the nation is desperate, letting young and old enlist. Stanley is lucky to become a dog handler, and is matched with a loyal, enthusiastic giant of a dog.

Based on the real experiences of dog handlers during World War One, this novel tells of the challenge faced by man and dog as they work together to get messages across no man's land. Soldier Dog is a tragic novel about the horrors of war and the loyalty of man's best friend.

Somehow, whilst filled with vivid descriptions of conflict and heart-wrenching moments of separation and loneliness, the story wearied me as I read. It did pick up towards the end and I found myself quite attached to Stanley and his canine friends, willing them to survive and be reuinited. I pitied Stanley - his brother physically absent whilst his father is emotionally distant - only able to find companionship with his dogs; and I adored the dogs - loyal in the face of the deadliest danger. But it is not my favourite in the 2013 selection.