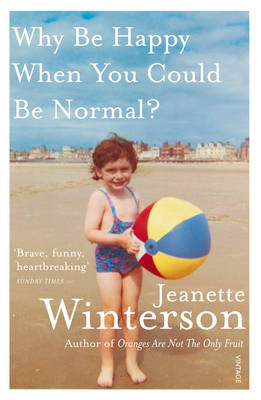

Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal?

Jeanette Winterson

London, Vintage, 2011, 230p

I have been rationing words on these last few days of my half term holiday. That is because I didn't want to rely on book swaps in hostels, since my luck with them proved to be limited. So over the last weekend of my adventure, I read and reread the Forward Book of Poetry 1994 (review coming soon), and I took my time enjoying Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

Jeanette Winterson, author of Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit, is a clever and sharp writer, both of fiction and non fiction. I always find myself seeking out her commentaries in The Guardian and elsewhere, and everything I read leaves me feeling reassured that I am not alone, that life is a mad experience for all of us.

Why Be Happy? is the sister book of the semi-autobiographical Oranges: Winterson confesses that her 1985 novel brushed over some of the harsher realities of her upbringing, including the creation of Elsie, the saviour of Oranges who makes Jeanette's harsh upbringing slightly softer. In reality, there was no Elsie. Winterson's childhood was full of explicitly repressive religious doctrine and nights locked out of the house, camped on the doorstep, as punishment for some odd crime, like reading.

Despite only having six books in her house growing up, Winterson could not help but fall in love with words. She hid books under her mattress and learned stories by rote, just so she could indulge in the magic of literature and poetry. Her love for language is infectious, and by the end of the memoir I had a long list of things I wanted to read or return to.

She also explores the challenges of suffering from depression, and explains the reality of finding her birth mother - a muddle of difficult administrative procedures resulting in a reunion she feels is rather less dramatic than typical reunion stories.

What touched me most was Winterson's process of coming to understand her approach to love and relationships. Her feelings towards her adopted mother are impressively positive; she finds herself coming to the defense of Mrs Winterson whilst it is clear that her child-raising techniques were somewhat unconventional. And this has had an interesting effect on Winterson's adult life - in particular, the feeling that she is not wanted and does not deserve to be loved in the way many others think of being loved.

This is the first book I have read more than once in years (other than Persuasion), and definitely the first book I have ever read when I started from the beginning again as soon as I had finished. It added something to the reading process that I have never experienced before - a feeling of familiarity, as I read words and scenes I had already stored in my memory, but some scenes shifted and altered as I read them a second time.

And I think this made me love Jeanette Winterson's writing even more - she could make me laugh when I already knew the punch line; she made me put the book down and think about what I had just read; and when I knew what was coming later, I could see elements of her future being shaped in her youth.

There was so much going on in this memoir, I do not have the space to explore it all in this blog, but it goes without saying that I think everyone should read this. Winterson's story makes it okay to be who you are, and I think we all need to be reminded of that every now and then.